|

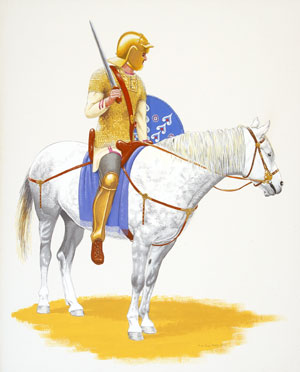

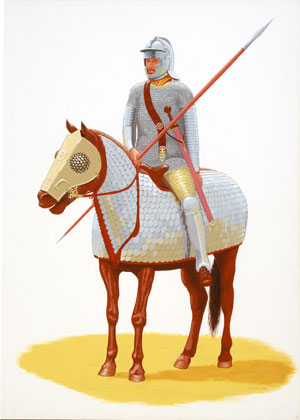

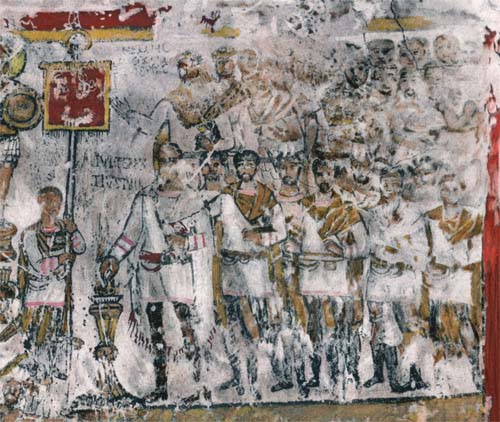

Dura-Europos is an ancient city in Eastern Syria, destroyed by war and abandoned in the third century AD. Excavations in the 1920s and ‘30s, renewed since the 1980s, have revealed spectacular remains of elaborately decorated buildings (including a painted synagogue and a very early Christian shrine), and astonishingly well-preserved artefacts. These famous finds led to the city being dubbed the ‘Pompeii of the Syrian desert’. Dawn at Dura: the citadel and the excavation house overlooking the Euphrates and Mesopotamia beyond (Photo © S James 2005) 1. Origins & Early Development The city of Europos was founded around 300 BC by Macedonian Greeks of the Seleucid empire, soon after Alexander overthrew Achemenid Persian power. It was alternatively known to local people as Dura, 'the fortress' (the modern compound name Dura-Europos was not used in Antiquity). By the first century BC it had been absorbed into the Arsacid Parthian empire. In the AD 160s it was seized by the Romans, and then in the 250s was destroyed by the new Sasanid Persian empire. Dura was outwardly a Greek city. Its history was always dominated by great imperial powers based in the Mediterranean and Iran. Nonetheless much of Dura’s population, and much of its culture, clearly belonged to the local Syro-Mesopotamian peoples. Dura overlooks the Euphrates river, and is protected on three sides by cliffs and steep wadis. On the fourth, it looks westwards across the flat steppe plain towards the ancient Syrian oasis city of Palmyra (Tadmor),with which it shared very close cultural links. Like the rest of the city’s perimeter this most vulnerable side was protected by a long curtain wall and towers, flanking the heavily defended main landward entrance, known as the Palmyrene Gate. (There was another major gate leading out onto the bank of the Euphrates, but this has been eroded by the river.) Over the first three centuries of its existence, Dura grew to be a major regional urban centre, probably less the ‘caravan city’ it was once held to be, and more a centre of manufacture, trade and regional administration for the rich Mesopotamian agricultural lands just across the river, the smaller settlements along the Middle Euphrates, and the pastoral communities of the surrounding steppe. Dura gradually expanded to fill its great wall-circuit, with residential streets and administrative buildings around the central market, and many temples scattered across the town. Dura's Palmyrene Gate (Photo © S James 2005) 2. Dura's later history: Roma  Roman soldiers at Dura c. AD 230, based on a wall painting and archaeological finds. © S. James 2000 Although originally a military road-station between the Seleucid empire’s Mediterranean capital at Antioch on the Orontes and its Mesopotamian capital at Seleucia on the Tigris, Dura was not an important military centre until late in its history. Largely for local policing purposes, it probably maintained its own local militia, backed up later by Palmyrene mercenary horse-archers. All this changed with the coming of the Romans.   Above, Roman auxiliary cavalryman (left) and Roman cataphract, based on the Dura finds © S. James 2003 In the AD 160s, aggressive Roman wars against the Parthian empire led to the permanent seizure of Dura and parts of Mesopotamia to its north. From the early 200s, it became a major forward base for repeated Roman aggressions against the crumbling Arsacid power. But by the 230s, Rome was on the defensive; Parthia collapsed, and in her place arose a new Persian empire, under the Sasanid dynasty, which proved a much tougher proposition. 3. The city under Rome The city measures roughly a kilometre from the northern to the southern ravines, and is up to 700m from the river cliffs to the 'desert' wall, an area of over 50 hectares (over 120 acres). An extensive necropolis of elaborate tombs sprawled across the plain to the west of the town. Outside the Palmyrene Gate lay a huge rubbish dump. Dura-Europos, overlooking the Euphrates Within the walls, many of the most important visible archaeological remains belong to Dura’s last decades. The city became more and more dominated by the presence of the Roman army, which took over many buildings and the entire northern part of the town as a garrison cantonment, while its economy was apparently undermined by constant wars and the severing of trade down-river into Persian territory. Yet paradoxically, with new arrivals from the Roman provinces, the rich cultural mixture of life in the city grew ever more cosmopolitan. 4. A cosmopolitan community In addition to the established mix of Syrians (especially Palmyrenes), Mesopotamians, and Steppe pastoralists, some of whom probably already thought of themselves as Arabs, plus elements of Greek and Iranian descent, there were now many other groups resident or passing through the town. These ranged from Roman provincial soldiers, perhaps even conscripted ‘barbarians’ from Northern Europe, to an evidently thriving community of Jews with strong connections to the major Jewish population of Babylonia. They constructed a rich synagogue, with stunning wall-paintings of Biblical scenes. And then there were the Christians, who maintained a house-church and baptistry in the town. Their evidently open and tolerated presence in the middle of a major Roman garrison town reveals that the history of the early church was not simply a story of pagan persecution.  A cross-section through the synagogue and city wall, showing how it was interred in the the earthern anti-siege rampart Ironically, it was the prolonged and devastating series of wars between Rome and Persia during the third century which resulted in the survival of all this rich testimony down to our times; for things like the wall-paintings of the synagogue and baptistry, behind the city wall between Tower 19 and the Palmyrene Gate, were buried by the Romans in their drastic preparations to withstand an anticipated Persian siege. Once the city fell, the remains were left undisturbed because the region became ‘no-man’s-land’ between the two states. 5. The destruction of Dura Dura’s death-throes left their own spectacular remains. The pre-siege strengthening of the ‘desert’ wall with the great earth rampart enshrouded the synagogue, baptistry and many other houses, temples, artefacts and documents. The siege itself, when it came, resulted in the burial of much more. Above, the undermined defences at Tower 19 (background), where many of the finest military artefacts were preserved. © S. James 2000 The Persians built a great siege ramp, and dug several mines under the walls, including one at Tower 19. Here, the Romans tried to stop them undermining the walls, by digging a countermine; but in a sharp underground battle, the Romans were beaten, and the Persians persisted in their task. We know this, because the countermine was still full of dead Roman soldiers when excavated, and the Persians completed and set fire to their mine as planned. Yet here they failed, for the wall, supported by its great earth and mudbrick revetments, simply sank into the ground, but stayed upright. The floors of Tower 19 itself collapsed, sealing a remarkable array of Roman military equipment–a painted wooden shield, some complete horse-armours–to add to the astonishing discoveries from the mine. It is this material which I have been studying. 6. Abandonment & rediscovery We do not know for sure how the Persians finally broke into the city, but once they did, Dura’s fate as a major centre of population was sealed. In later centuries, other Roman armies would hunt gazelle through its deserted streets, and it became a ruin desolate enough to attract Christian hermits. Its very identity was completely forgotten. However, it was rediscovered in 1920, in an ironic, and rather fitting historical symmetry. In April 1920, Indian troops under British command encamped in the anonymous ruins, during the Anglo-French carving-up of the Middle East following the collapse of the Ottoman Turkish empire. Fighting local Arab groups who sought at last to be free of foreign domination, the Indian soldiers dug defensive trenches along the earth-enshrouded walls. They were astonished to find wall paintings, the first showing Syrian priests, the second showing a Roman officer making sacrifice to deities, one of whom was the Fortune of Dura. Dura-Europos was rediscovered.  For Rome's Palmyrene soldiers were Syrians, and most of the history of Dura-Europos was about Syrians; and now the further unravelling of that history is a joint enterprise between Syrian, other Arab and Western archaeologists. The soldiers shown ranked behind the officer in the painting are identifiable as men of a Palmyrene regiment in the Roman service (right). Curiously, then, on that spring day in 1920, Asiatic auxiliaries of one European imperial power came face to face, so to speak, with Asiatic auxiliaries of another, from almost seventeen centuries earlier. 7. The exploration of Dura-Europos Dura has been extensively excavated in a series of campaigns since the 1920s. This has been a truly international effort. The first archaeologist to work at the site, when the Indian troops found the paintings in 1920, was the American James Henry Breasted. Within a couple of years, with the site now part of French-ruled Syria, the detailed expolration of the site begain in earnest. The Belgian scholar Franze Cumont conducted some important initial excavations, followed by a major Franco-American project (the French Academy and Yale) which saw ten seasons of excavations from 1928 to 1937 when funding ran out. It was this large-scale project, overseen by the Russian scholar Mikhail Rostovtzeff, which made most of the famous discoveries. Little further work was conducted at the site until a new, Franco-Syrian project was initiated in the mid-1980s by Pierre Leriche. On a more modest scale than the pre-war campaigns, it has the advantage of more sophisticated modern technology and techniques, and has made major achievements in conserving and presenting the site, and in further developing our knoweldge of the history and development of the city through survey, renewed excavation, and analysis of finds and chronology. I am currently an associate researcher on the project, and am working on the archaeology of the Roman military base.  2005 excavation on the line of the mud-brick boundary wall of the Roman military base inside the city, with the 'desert wall' in the background 8. Further informaton Visiting Dura-Europos Dura remains relatively remote from the major cities of Syria, but is increasingly visited by tourists, especially coach-parties. One of the houses of the city has been reconstructed, to serve as an on-site orientation centre, shop and restaurant. Be warned that the site is very large, with little shelter from sun, strong winds, the rare, seasonal, but phenomenal rainstorms, and more frequent dust-storms. However, the rewards of a visit are great: although the largely mud-brick architecture means that it is no challenge to Palmyra visually, the dramatic remains of the walls and siegeworks, and precipitous views over the Euphrates cliffs, are very striking. Dura lies close to the main Deir-ez-Zor to Abu Kemal road, and is accessible by bus or taxi, but there is still nowhere to stay in the immediate vicinity. Museums displaying Dura material

9. Dura-Europos Specialist literature Early excavations 1920-23 Breasted, J.H., 1922 ‘Peintures d’epoque Romaine dans le désert de Syrie’, Syria III, 177-206 Breasted, J.H., 1924 The oriental forerunners of Byzantine painting, Oriental Institute Publications vol. 1, Chicago. Cumont, F., 1926 Fouilles de Doura-Europos 1922-3, Paris. Reports on the Yale-French Academy excavations, 1928-37 Season-by-season Reports were published for all but the final campaign of excavations: The excavations at Dura-Europos, Preliminary Report on the... ...First Season, Spring 1928, P. Baur and M. Rostovtzeff, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1929. ...Second Season, 1928-1929, P. Baur and M. Rostovtzeff, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1931. ...Third Season, 1929-1930, P. Baur, M. Rostovtzeff and A. Bellinger, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1932. ...Fourth Season, 1930-31, P. Baur, M. Rostovtzeff and A. Bellinger, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1933. ...Fifth Season, 1931-1932, M. Rostovtzeff (ed.), Yale University Press, New Haven 1934. ...Sixth Season, 1932-1933, M. Rostovtzeff, A. Bellinger, C. Hopkins and C. Welles, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1936. ...Seventh and Eighth Seasons, 1933-1934 and 1934-1935, M. Rostovtzeff, F. Brown and C. Welles, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1936. ...Ninth Season, 1935-6, Part 1: The Agora and Bazaar, M. Rostovtzeff, A. Bellinger, F. Brown and C. Welles, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1944. ...Ninth Season, 1935-6, Part 2: The Necropolis, M. Rostovtzeff, A. Bellinger, F. Brown and C. Welles, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1946. ...Ninth Season, 1935-6, Part 3: The Palace of the Dux Ripae and the Dolicheneum, M. Rostovtzeff, A. Bellinger, F. Brown and C. Welles, (eds), Yale University Press, New Haven 1952. NB No report was prepared on the tenth and final season, but a brief account has been pieced together: Matheson, S., 1992 ‘The tenth season at Dura-Europos 1936-1937’, Syria LXIX, 121-140. Final Reports on the Yale-French Academy excavations (NB the originally projected series remains substantially incomplete) Excavations at Dura-Europos, Final Report Volume... ...III, Part 1, fasc. 1 The Heracles Sculpture, Downey, S.B., 1966 Dura-Europos Publications Locust Valley, N. Y., New Haven ...III, Part 1, fasc. 2 The Stone and Plaster Sculpture, Downey, S.B., 1977 Los Angeles : Institute of Archaeology, University of California ...IV, Part 1, fasc. 1 The Green Glazed Pottery, Toll, N.P., 1943 New Haven: Yale University Press ...IV, Part 1, fasc. 2 The Greek and Roman pottery, Cox, D.H., 1949 New Haven: Yale University Press ...IV, Part 1, fasc. 3 The Commonware Pottery, the Brittle Ware, Dyson, S.L., 1968 New Haven: Yale University Press ...IV, Part 2 The Textiles, Pfister, R. and Bellinger, L., 1945 New Haven: Yale University Press ...IV, Part 3 The Lamps, Baur, P.V.C, 1947 New Haven: Yale University Press ...IV, Part 4 The Bronze Objects; Fasc. 1, Pierced Bronzes, Enameled Bronzes, and Fibulae, Frisch, T., and Toll, N., 1949 New Haven: Yale University Press ...IV, Part 5 The Glass Vessels, Clairmont, C.W., 1963 New Haven: Yale University Press ...V, Part 1 The Parchments and Papyri, Welles, C.B, Fink, R.O and Gilliam, J.F., 1959 New Haven: Yale University Press ...VI The Coins, Bellinger, A.R., 1949 New Haven: Yale University Press ...VII The Arms and Armour, and Other Military Equipment, James, S.T. 2004, British Museum Press, London ...VIII, pt. 1 The Synagogue, Kraeling, C.H., 1956, New Haven: Yale University Press ...VIII, pt. 2 The Christian Building, Kraeling, C.H., 1967, New Haven: Yale University Press The current international research project Results are being published as papers, many of which are listed below, in volumes of the series Doura-Europos études. Originally subsections of the journal Syria, these are now freestanding volumes. General bibliography Abdul Massih, J., 1997 ‘La porte secondaire à Doura-Europos’, Doura-Europos études IV, 47-54. Allara, A, 1988 ‘Les maisons de Doura-Europos. Les Données du terrain’, Doura-Europos études 1988; Syria, Tome LXV, fasc. 3 & 4, 323-342. Allara, A., 1997 ‘Constitution d’un repertoire de l’architecture domestique à Doura-Europos’, Doura-Europos études IV, 145-154. Arnaud, P, 1988 ‘Observations sur l’original du fragment de carte du pseudo-bouclier de Doura-Europos’, REA 90, 151-161 Arnaud, P., 1989 ‘Une deuxième lecture du "bouclier" de Doura-Europos’ CRAI 1989 373-387 Bertolino, R., 1997, ‘Les inscriptions Hatréenes de Doura-Europos: étude épigraphique’, Doura-Europos études IV, 199-206 Dabrowa, E., 1981 ‘La garnison romaine a Doura-Europos. Influence du camp sur la vie de la ville et ses consequences’, Cahiers scientifiques de l’universite Jagellanne, DCXIII, 61. Dirven, L.A. 1999 The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos : a study of religious interaction in Roman Syria Leiden : Brill Gelin, M., 1997 ‘Les fouilles anciennes de Doura-Europos et leur contexte: documents d’archives conservés dans les institutions françaises et témoignages’, Doura-Europos études IV, 229-44. Gelin, M., Leriche, P., and ‘Abdul Massih, J., 1997, ‘La porte de Palmyre à Doura-Europos’, Doura-Europos études IV, 21-46. Geyer, B., 1988 ‘Le site de Doura-Europos et son environnement géographique’, Doura-Europos études 1988; Syria, Tome LXV, fasc. 3 & 4, 285-295. Gilliam, J., 1941 ‘The Dux Ripae at Dura’, Transactions of the American Philological Association LXXII 157-175. Goldman, B., 1992 ‘The Dura Synagogue costumes and Parthian Art’ in Gutman 1992 53-77. Goldman, B., 1993 ‘The late pre-Islamic riding costume’, Iranica Antiqua, XXVIII, 201-246. Goldman, B, and Little, A.M.G, 1980 ‘The beginning of Sasanian painting and Dura-Europos’, Iranica Antiqua XV, 283-298. Grenet, F., 1988 ‘Les Sassanides a Doura-Europos (253 ap. J.C.); réexamen du matériel épigraphique iranien du site’, Geographie historique au proche-orient, Paris. Gutman, S., 1992 The Dura-Europos Synagogue, a re-evaluation (1932-1992), Scholar Press, Atlanta. Hopkins, C., 1979 The Discovery of Dura Europos, New Haven and London. James, S., 1983 ‘Archaeological evidence for Roman incendiary projectiles’, S.Jb. 39 142-3. James, S., 1985 ‘Dura-Europos and the Chronology of Syria in the 250s AD’, Chiron 15, 111-124. James, S., 1986 ‘Evidence from Dura-Europos for the origins of late Roman helmets’, Syria LXIII 107-134. James, S., 1987 ‘Dura-Europos and the introduction of the ‘Mongolian release’, in ed. M. Dawson, Roman Military Equipment; the accoutrements of war BAR International Series 336 77-83 James, S., 1997 ‘Military equipment from the Yale/French Academy excavations at Dura-Europos, 1928-36’, Doura Études IV, 1991-3, IFAPO, Beirut, 223-228. Kaplan, B., unpub. Report on the leatherwork from Dura-Europos, Dura archive, Yale, 1971. Kennedy, D.L., 1983 ‘Cohors XX Palmyrenorum; an alternative explanation of the numeral’, ZPE 53 214-216. Kennedy, D.L., 1986 ‘‘European soldiers and the Severan siege of Hatra’ in Freeman, P., and Kennedy, D., (eds) 1986 The Defence of the Roman and Byzantine East, BAR International Series 297., 397-409. Kennedy, D.L, 1994 ‘The cohors XX Palmyrenorum at Dura Europos’ in Dabrowa, E. (ed.), 1994, The Roman and Byzantine Army in the East, Universytet Jagiellonski, Krakow, 89-98. Kiefer, K., and Matheson, S., 1982 Life in an Eastern province: The Roman fortress of Dura-Europos. Checklist of the exhibition at Yale University Art Gallery, 24 March to 5 September 1982 Newhaven. Leriche, P., 1993a ‘Techniques de guerre sassanides et romains à Doura-Europos’, in ed. F. Vallet and M. Kazanski, L’Armée Romaine et les Barbares du IIIe au VIIe siècle: Tome V des Mémoires publiées par l’Association Française d’Archéologie Mérovingienne, 83-100. Leriche, P., 1993b ‘Dura-Europos’ in ed. Roualt, O. and Masetti-Rouault, M.G.,1993, L’Eufrate e il tempo: le civiltà del medio Eufrate e della Gezira siriana, 223-6 Leriche, P., 1993c ‘Le Chreophylakeion de Doura-Europos et la mise en place du plan Hippodamien de la ville’ Archives et sceaux du monde hellénistique, Bulletin de correspondance Hellénique 29, 157-169. Leriche, P., 1996 ‘Dura-Europos’ Encyclopaedia Iranica VIII-6, 589-94. Leriche, P., and Bertolino, R., 1997 ‘Les inscriptions Hatréenes de Doura-Europos: le contexte archéologique et historique’, Doura-Europos études IV, 207-14. Leriche, P., Mahmoud, A., Mouton, B., and Lecuyot, G, 1986 ‘Le site de Doura-Europos: état actuel et perspectives d’action’, Doura-Europos études 1986; Syria, Tome LXIII, 5-25. Leriche, P., and Mahmoud, A., 1988 ‘Bilan des campagnes de 1986 et 1987 de la mission Franco-Syrienne à Doura-Europos’, Doura-Europos études 1988; Syria, Tome LXV, fasc. 3 & 4, 261-282. Leriche, P., and Mahmoud, A., 1990 ‘Bilan des campagnes de 1988-1990 à Doura-Europos’, Doura-Europos, Études 1990; Syria, Tome LXIX, 261-282. Leriche, P., and Mahmoud, A., 1994 ‘Doura-Europos, bilan des recherches récentes’, Comptes-Rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belle-Lettres, 1994, 396-420. Leriche, P., and Mahmoud, A., 1997 ‘Bilan des campagnes 1991-1993 de la Mission Franco-Syrienne de Doura-Europos, Doura-Europos études IV, 1-20. Lillios, K., unpublished ‘An analysis of three scabbard slides from Dura-Europos’, unpublished Yale University paper., 1983. MacDonald, D., 1986 ‘Dating the fall of Dura-Europos’, Historia, XXXV, heft 1, 45-68. Matheson, S., 1982 Dura Europos. The ancient city and the Yale collection New Haven. du Mesnil du Buisson, R., 1944 ‘Les ouvrages du siege a Doura-Europos’, Memoires de la Societe Nationale des Antiquares de France, NS 1 5. Perkins, A., 1973 The Art of Dura Europos, Oxford. Pollard, N., 1996 ‘The Roman army as ‘total institution’ in the Near East? Dura-Europos as a case study’, in Kennedy, D.L., (ed.) 1996 The Roman Army in the East, JRA Supplementary Series No. 18, 211-227 Rebuffat, R., 1986 ‘Le bouclier de Doura’, Syria LXIII 85-105 Rostovtzeff, M., 1932 Caravan Cities, Oxford. Rostovtzeff, M., 1938 Dura Europos and its Art, Oxford. Speidel, M.P., 1984 ‘‘Europeans’- Syrian Elite Troops at Dura-Europos and Hatra’, in Speidel, M.P. (ed.), Roman Army Studies I, Amsterdam, 301-309. Welles, C., 1951 ‘The Population of Roman Dura’, in P.R. Coleman-Norton (ed.), Studies in Roman Economic and Social History in Honor of Allan Chester Johnson, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 251-74. Welles, C., 1957 ‘The Chronology of Dura Europos’, in Symbolae R. Taubenschlag III (Eos XLVIII 464). Yon, J.-B., 1997 ‘Les conditions de travail de la mission américano-française à Doura-Europos à travers les archive de ‘Université de Yale’, Doura-Europos études IV, 245-55. (责任编辑:admin) |